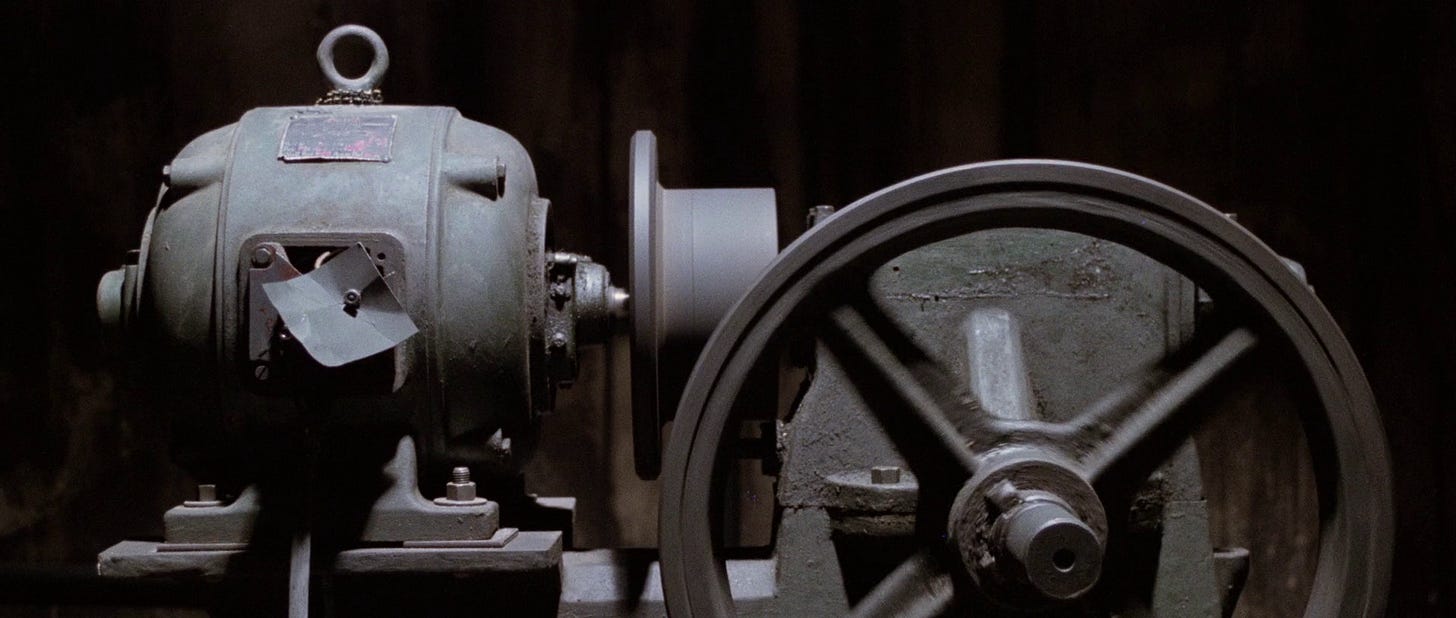

The Operator’s Flywheel

How asking better questions builds context, influence, and impact over time.

When people talk about great operators, they usually rattle off technical skills or functional achievements. A finance leader who can model twelve scenarios in a spreadsheet. A growth leader who knows attribution models inside and out. A product leader who can ship fast.

But what really sets exceptional operators apart is something subtler. They build a flywheel of influence by asking better questions… e.g. built on curiosity. Those questions lead to context, context leads to sharper judgment, sharper judgment leads to more influence. And the cycle keeps spinning.

Curiosity is a practice, not a trait

We’re quick to describe curiosity as innate. Someone is “naturally curious” or “just not that curious.” I used to buy into that. But over time, I’ve realized curiosity isn’t something you’re born with or not.

It’s a practice.

Like going to the gym, it ebbs and flows. It gets stronger the more you work it. It compounds when you surround yourself with feedback loops. And it can just as easily atrophy in the wrong environment.

The best operators I’ve worked with—whether in finance, product, or growth—are the ones who built curiosity into their daily rhythm.

The Overheard List

When I was an analyst, I kept what I called an “overheard list.”

Every time I caught a comment in a meeting—“customers are churning because of price,” “our enterprise deals always slip at the last minute,” “marketing leads aren’t converting”—I’d jot it down.

Not to prove or disprove everything. The act of writing was the practice. It tuned my ear toward unresolved assumptions. It gave me a backlog of potential investigations. It sparked connections I wouldn’t have found otherwise.

Sometimes the questions went nowhere. Sometimes they changed the trajectory of a decision. Either way, the practice built momentum.

Eminem read the dictionary for inspiration. Operators can read their overheard list.

The curiosity flywheel

The more you lean into curiosity, the more it compounds:

Curiosity → Better questions → Deeper understanding → More influence → More context → Even more curiosity.

It’s a virtuous cycle. And it doesn’t just apply to analysts.

A curious finance leader notices the odd trend in sales efficiency before it becomes a board question.

A curious PM spots the unexpected usage pattern that becomes a growth lever.

A curious CRO asks why one AE consistently outperforms and rewrites the playbook.

What kills curiosity

Curiosity is fragile. Organizations crush it without even noticing.

Bad data. Overly prescriptive stakeholders. Too many meetings. Unclear priorities. A culture of “just execute.” All of these suffocate curiosity before it can grow.

Great leaders act like great parents: fanning the flame when they see it, softening the blow when it runs into dead-ends, creating space for exploration.

Building your own practice

The specifics don’t matter as much as the intent. You could:

Keep an overheard list.

Write three questions after every important meeting.

Block an hour a week to chase curiosities guilt-free.

Treat every unexplained metric as a mystery worth investigating.

The point is to practice. To make curiosity a muscle.

Because curiosity isn’t what makes you practice. It’s the practice that makes you curious.